formula one history

Formula One is a global leviathan. In 2017, its global audience was 352.3 million people. The sponsorship income of the manufacturers is in the hundreds of millions of Euros per year. The top speed of the Formula One car is 231 miles per hour. Put simply, everything in Formula One is done to a huge scale. One of Formula One’s greatest strengths is the fact that – despite all of the engineering expertise and technology – it is a simple sport.

There is something inherently visceral about watching incredibly skilled drivers hurtle hugely quick cars around a race track. Despite the ever-growing speed, Formula One is a safer sport now than ever in its history. Indeed, throughout its nearly 80 year past, Formula One has, every year, become both faster and safer. This is the real engineering skill of the sport.

Origins

When did the Grand Prix begin?

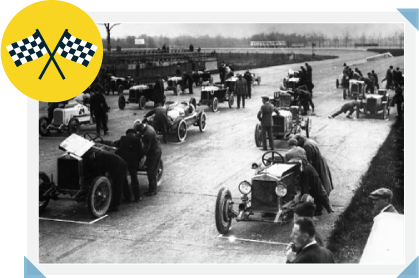

Ever since there have been cars, there has been car racing. As technology improved, and cars became more numerous, European manufacturers as early as 1894 in France, began racing as a way of competing and marketing their products.

In the interwar years, a series of Grands Prix race days took place throughout Europe, designed to show off car and driver skills to a receptive European population.

What was the Grand Prix like Pre-WWII?

Had World War II not intervened it is likely that Formula One would have begun much earlier. Certainly, in the interwar years, there was an increasing move towards codifying the sport from the ragtag one-off events.

With the rise of Nazism and the focus of French and Belgian (and other European) engineers on preparing for war, however, Formula One was put on hold until 1946.

When did the Formula One race begin?

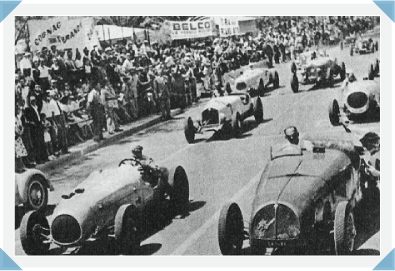

The name ‘Formula One’ refers to a standardized set of rules with which drivers and engineers must comply. In 1946, the idea of a Formula One Championship began. From 1946-1950 the races were not part of an overall calendar and races tended to be ad hoc affairs.

However, there was a growing desire to create a single competition based on performance across a wide range of races. Ultimately the goal was to determine who was the best driver and who was the best manufacturer.

When did the Drivers‘ World championship begin?

The final details on the drivers’ world championship were not agreed upon until 1950, and the first World Championship Grand Prix took place in 1950 at Silverstone in the UK. Even then, only seven of the total Grands Prix counted towards the World Championship, although the fundamental structures were in place. Even as the championship grew, there remained non-championship races until 1983.

In the period since the emergence of the World Championship, there have been periods of dominance by one company or the other.

- The British, for example, dominated the early 1960s and early 1970s, before Ferrari dominated the mid-1970s.

-

- In the latter part of the 1990s and early 2000s, Ferrari again enjoyed a period of dominance, although more recently Williams and Mercedes have been leading manufacturers.

Bernie Ecclestone took over the management of Formula One’s commercial rights in 1971, beginning an era of truly global financial power. Since then, Formula One has grown in popularity, and the prize money awarded for the drivers’ championship has too.

How has racing evolved?

After World War II, Formula One was an established sport, with a great deal of popularity.

Gradually, in the post-war years, F1 underwent a series of evolutionary changes. For example, in 1958, the Grands Prix was shortened from 300 miles to 200 miles, and the fuel used by drivers was standardized to Avgas.

1958 was also a landmark year as it was the first year that a car with an engine mounted behind the driver won the championship. Stirling Moss’s Cooper won the Argentine Grand Prix in his newly designed car, which soon became the standard across all manufacturers.

Previously each team had made their own fuel using methanol and other compounds. 1958 also saw the introduction of a constructors’ world championship.

In 1965, a Japanese team won the Mexican Grand Prix with a transverse engine. Unlike Stirling Moss’s car, however, no other manufacturers copied the design of the Japanese car, which remains the only car to have done so with an engine of that type.

This Grand Prix was also the last that saw the use of a 1.5-liter engine before the loads were increased to 3.0 liters. This naturally increased the speeds that cars are capable of achieving, and they now regularly top 200 mph – a speed more than double the top speed of the earliest racing cars.

By far the biggest evolution that has taken place in the period since WWII has been the international spread of Formula One. Races are now truly spread throughout the globe, with races on almost every continent.

This has meant that Formula One now has fans, constructors, and drivers from all over the world. With races in Bahrain, China, Brazil, and Abu Dhabi, Formula One is quickly becoming a sport that transcends national boundaries. Indeed, more and more, fans’ loyalty is to the car manufacturers rather than the racing drivers.

What developments were there in race car technology?

Car technology in Formula One has been a result of each team constantly striving to gain a competitive advantage.

The two biggest developments that have taken place in the history of Formula One have been the placement of the engine and the material of the chassis. As mentioned above, in 1958 Stirling Moss’s car featured a behind-driver engine.

For the first time since the replacement of horses, cars were now pushed rather than pulled, giving greater control over the steering. Modern safety innovations have meant that the engine is now placed in the center of the car, although this is still behind the driver.

The most radical change that took place with the chassis was the development, in 1962, of the aluminum sheet monocoque, which effectively meant that the car was one long body panel.

This dramatically reduced weight and made the cars more rigid, meaning that even greater speeds were possible. In 1981 McLaren superseded this with the development of the carbon fiber chassis.

Other developments, like active suspension, turbochargers, and traction control were all innovations that have been banned sporadically throughout the history of Formula One, showing that the eponymous regulations of Formula One have also been forced to innovate throughout its history.

How has safety developed?

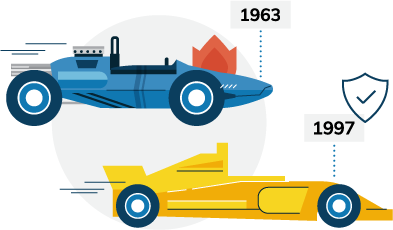

Concurrent with the development in speed and aerodynamics of Formula 1 cars has been innovation in safety. In the period 1963-1967, an estimated 256,000 kilometers were driven under race conditions, resulting in three driver fatalities.

Since 1997, there have been an estimated 348,000 kilometers driven under race conditions, with zero fatalities.

Interestingly, the number of accidents per kilometer has actually increased in that period, due to the increased speed driven by cars. Safety innovations have therefore made it so that crashes are less likely to result in death or serious injury for drivers. Crashes that take place now would have been fatal in the past. Through constant innovation, Formula One is now safer than at any point.

THE 1960s

The first set of innovations that took place in the 1960s were centered on the danger caused by fires in the post-crash period. For example, in the period 1963-1965, cars were required to be fitted with fire protection, safer fuel tanks (and gas lines), and fireproof suits were made mandatory for all drivers.

Cockpits and safety belts began to be designed for easy release and exit in the case of a crash. In this period also were modern crash helmets (i.e. shatterproof) and roll bars fitted to prevent the initial danger of a crash.

Safety was increasingly becoming a priority in this period. The FIA began a system of standardized inspections, run by FIA officials. Prior to this, the inspections had been undertaken by national authorities. In 1963, the modern flag signaling system was introduced to warn other drivers of a crash ahead (as well as pass other safety-related messages).

THE 1970s

In the 1970s spectator safety became increasingly important, and a number of regulations were introduced that were designed to protect those who attended these events. For example, in 1970 it became compulsory for circuits to have spectators three meters behind any fencing (and fencing was increasingly regulated).

Read more: How Cars Are Safer Now Than in 1970

In 1973 ‘catchfences’ were introduced to prevent cars from being able to endanger spectators. Where previously hay bales had been used as a crash barrier, this was now made illegal because of the fire hazard presented.

The dangers of fire were also continually addressed for drivers, as safety bladders in fuel tanks were introduced in 1970, and safety foam in the tanks became mandatory in 1972. In 1973, the FIA mandated the use of crushable structures around fuel tanks (again, to prevent the danger of a crash causing rupturing and leaking).

Starting in 1978, drivers were compelled to have a license to qualify to drive, allowing the FIA to introduce more rigorous standards on driver training.

THE 1980s

In the 1980s technology had advanced to the extent that it was now possible to protect the driver in all but the most serious crashes.

Knowledge of crumple zones and the introduction of a ‘survival cell’ around the driver meant that crashes themselves became increasingly less fatal. This ran concurrently with increasing innovation with regard to fire, and a growing presence of medical staff on hand at races.

The biggest change in respect to fire was that in 1984 it was banned for drivers to refuel during races. The fuel tank was also placed in the center of the car, meaning it was further protected from impact.

THE 1990s

In the 1990s, cars were increasingly modified to be faster, and safety innovations were increasingly based on more precise details.

For example, design specifications became even more rigorous. In 1993, the mandatory headrest area was increased to four meters, the front overhang was reduced from one meter to 90 centimeters, and additional regulations gave very specific details about the distance of the rear wing height, the distance of the front wing endplate, and the wheel width.

More and more of the technology was taken away from drivers, thereby forcing them to be fully engaged with their drive. For example, in 1994, traction control, automatic gear, and anti-lock brakes were banned.

2000 ONWARDS

The safety changes that have taken place since 2000 have almost all been centered around increasing the different forces that cars are able to respond to, meaning that drivers are protected in an even larger array of cases.

For example, in 2000 the ‘survival cell panel outer skin laminates’ were fitted with added penetration resistance, and the static load side test in the driver’s leg areas increased by 20%. In 2001, the side impact test speed was increased to 10 m/s.

This suggests that the fundamental structures of the car are sound, and the primary innovations are involved in adjustments, rather than major radical change.

Formula One has become a global phenomenon, a long way from its roots in European racing in the interwar period.

The developments in technology, speed, and safety have all been noteworthy; fundamentally, however, the premise of Formula One is to take the world’s best drivers and the world’s best engineers and put them at the pinnacle of what a car is capable of. In this respect, the spirit of Formula One is the same as it always was.

Certainly, there is more money in the sport, and the cars now travel at speeds that drivers in the 1920s could not dream of. However, the glitz, the glamour, and the sheer bravado of the drivers all demonstrate a sport that still retains an innocent and wide-eyed view of the fundamental beauty of racing.

Throughout the history of Formula One there have been many developments, but at no stage has the average spectator ever looked at the vehicles, and the drivers, with anything less than awe. And that will never change.

Sources and Further Reading

- http://www.atlasf1.com/news/safety.html

- http://en.espn.co.uk/f1/motorsport/story/3831.html

- http://en.espn.co.uk/f1/motorsport/story/3836.html